Introduction

One of the highlights of my career has been the opportunity to serve as a CISO, designing, managing and growing a successful security program. Through this series of posts, I’m sharing some of the things I’ve learned along the way.

In Part 1 of this series I gave a brief background on how I became a CISO and defined the security program’s purpose and mission statements. In this second installment, I’ll give some suggestions on how to scope and organize your program.

What would you say you do here?

Now that we’ve defined our Why and have a guiding Mission Statement, we need to identify the scope of activities that will comprise our security program. In other words, we need to define exactly what we’re going to be responsible for on a day-to-day basis.

While it sounds pretty straightforward and obvious, this is such an important step because you can’t effectively assess program maturity, plan projects, create a budget, or determine resource requirements until you understand what you’re actually responsible for doing.

It’s also just as important to explicitly identify and document those functions that will not be part of your program. When it comes to a security program, there should be no assumptions about who has responsibility for a given activity.

Keep in mind that program scoping is not going to tell you how much effort you need to invest in an specific area or which projects you need to prioritize…that will come from assessing risk and measuring your program’s current state (which I’ll cover in the next post).

Now let’s take a closer look at what I mean by “scoping the program” …

How To Scope Your Security Program

A security program’s scope can be pretty wide, ranging from highly technical activities (malware analysis) to those centered around people (training and awareness) or governance (policies and procedures) … so where to begin?.

While not an exhaustive list, I recommend considering the following:

- What are you being asked to do by your organization?

- What are you required to do by law/regulations?

- What do best practices say you should be doing?

- What key enablers would benefit your organization?

- What are you currently resourced to do?

What does your organization expect?

Chances are, you’ve been hired with a minimum set of responsibilities and functions that your organization expects you to oversee, but how well these are initially defined may vary. Perhaps you are tasked with managing “Security Policy and Standards” but the specific polices and standards are not defined. Perhaps your organization has some more specific responsibilities in mind, but doesn’t have enough expertise to understand all of the things required from a best-practice security program (and is looking to you to further advise). Unless you’re walking in to a mature program, these expectations will likely not be detailed enough to fully define your program scope, but can serve as a starting point. In other words, don’t ignore those things, but don’t stop there.

What are you required to do?

The next thing you should understand are any relevant laws, standards, or regulatory requirements that apply to your industry or organization. Partner with your compliance and legal colleagues to make sure you’re not overlooking anything. Regulations and standards like SOX, HIPAA, and PCI all have specific requirements that your program may need to address and, depending on your industry, you may have to comply with multiple regulations.

While very important, regulatory compliance should be thought of as a minimum set of requirements. It’s the floor, not the ceiling, of a best practice security program. That said, you’ll definitely want to be able to clearly demonstrate how your security program activities support compliance, so be sure to identify what those requirements are and incorporate them into your program scope.

What does best practice suggest?

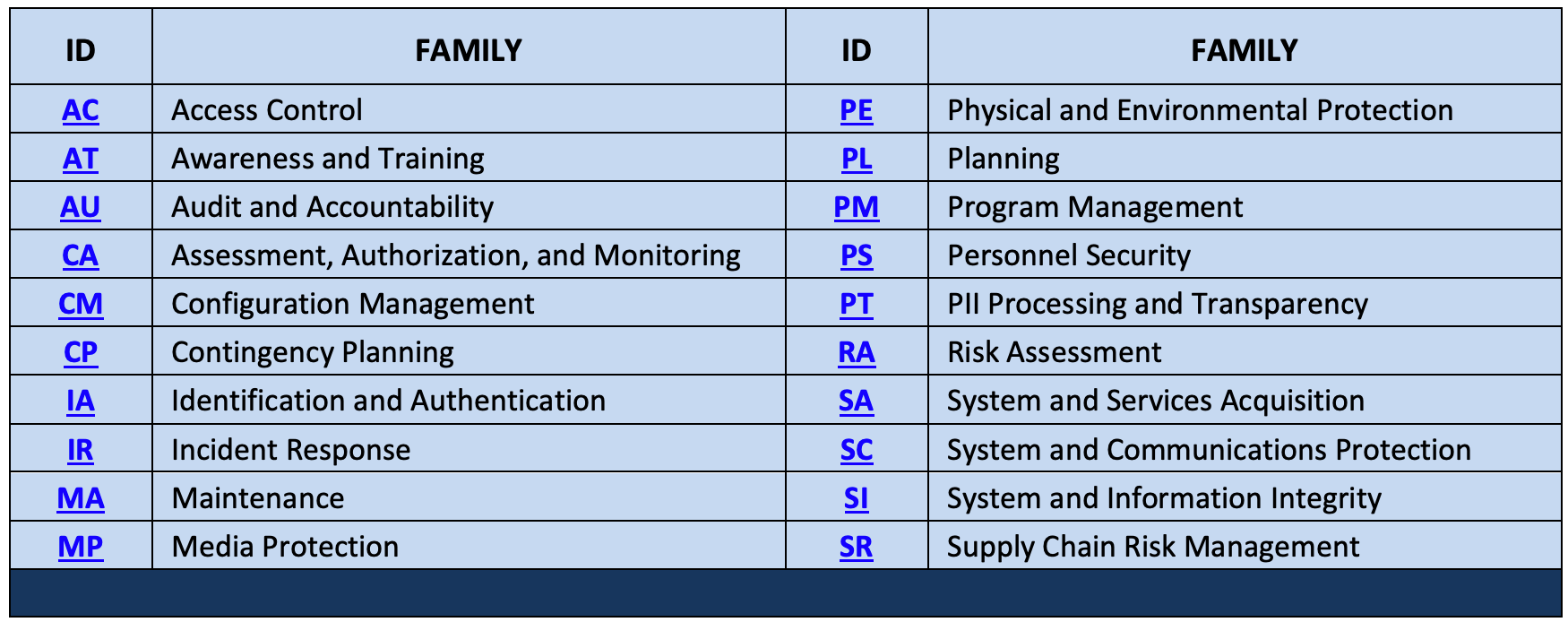

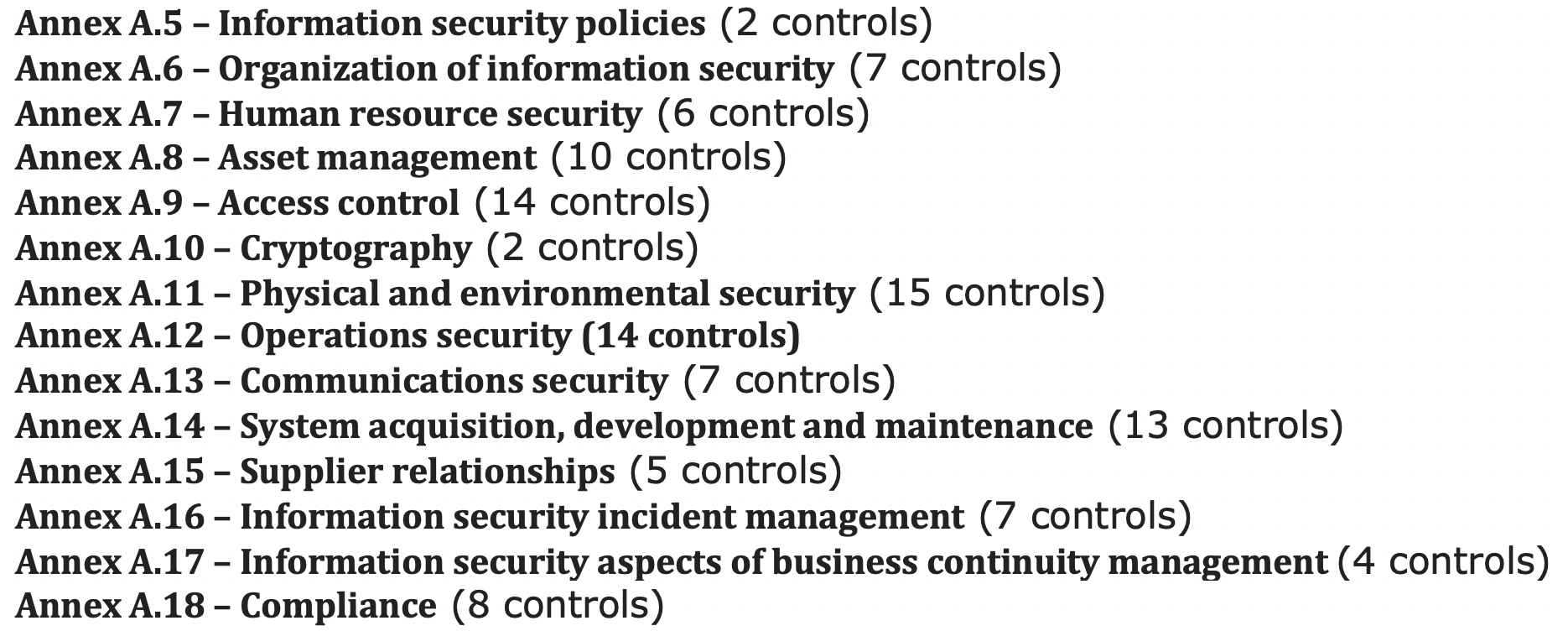

Beyond whatever has been defined for you by your organization and the regulatory requirements you are beholden to, I recommend reviewing standards frameworks (like NIST, ISO, COBIT, and CIS) to get a broader understanding of all of the things that could (or should) be part of a security program. While you will find overlap between them, some of these standards go deeper into certain areas, so you may want to review more than one. Familiarize yourself with them, get an understanding of the various controls and activities, and determine which apply to your program.

As illustrative examples, I’ve included the control families from both NIST 800-53 and ISO 27001 below.

Within each of the above control “families” or groupings, you’ll find more detailed controls that can help you identify specific functions that you may want to include in your program. For example, within Access Control or Identification and Authentication you will find activities related to governance, authentication, and remote access. Beyond these general control frameworks, perhaps there are other areas for which you need more specific best-practice guidance. Are you tasked with cloud security? If so, you may want to review something like CIS benchmarks or the Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM).

A quick note about these standards: I’m not suggesting using these control frameworks to implement a checklist-based approach to security and this isn’t about developing a long list of policy requirements that simply get recorded in a giant risk assessment document that gets dusted off and updated once a year. Instead, use these frameworks to educate yourself on best practices and make sure you’re not missing anything as you’re scoping your program. These are primarily meant to help you define the “what” not the “how”.

That said, if you’re in a highly regulated industry (and who isn’t these days?), you may also want to closely align with at least one of these standards because it can help you demonstrate adherence to best practices in future audits and clearly illustrate how you’re meeting those regulatory requirements (in a language that auditors understand). For example, if the primary regulating body in your industry recommends using the NIST controls framework, then documenting the extent to which you align with that framework might be beneficial. Just keep in mind that doesn’t mean you have to implement every control in NIST SP 800-53, nor does it mean you can only align with NIST.

What key enablers might benefit your organization?

As I covered in Part I of this series, I’m a big proponent of finding ways to better enable the organization and I think there are multiple opportunities to do so via an Information Security program. This includes initiatives focused improving the employee or consumer experience, introducing new capabilities, eliminating redundancies, finding efficiencies through automation, etc.

However, the degree to which you’re able to do undertake these activities in the early stages of a security program may vary. In a less mature organization (or one with few resources), you may need to first focus your attention on risk management basics before tackling initiatives focused on improving user experience. If you’re brand new to the role, you may also need more time for stakeholder engagement in order to better understand pain points and opportunities to improve the day-to-day user experience.

It’s also possible that even if you are able to include some of these enabling activities, it won’t significantly change the overall scope of your program. For example, if you’ve already determined that a broad range of Identity and Access Management activities are within scope, initiatives focused on improving the user authentication experience probably won’t change that. However, pulling from my own experience, let’s say you identify an opportunity for improved secure document sharing and collaboration. That may be a function that you didn’t originally plan to include in your security program at all, but for multiple reasons, you end up taking on that responsibility (which impacts your program scope and resourcing needs).

While it may not have a considerable impact, I do recommend at least considering whether there are any key enabling activities that might influence the scope of your program.

What are you currently resourced to do?

After answering the above questions, you may end up with a long list of things you’d like to do, but are simply not resourced to do them all. In the absence of getting more resources, you may be forced to exclude some activities from scope for now.

For example, perhaps you have a need for initiatives focused on both privileged access management and modern authentication, but you’re not staffed to do them both right now. Or perhaps you have to de-scope Security Training and Awareness entirely because you don’t have the resources or funding. While the latter is an extreme example that hopefully you won’t face, as a reminder, be sure to consider your regulatory requirements when making these decisions and document any justifications as to why something is omitted from scope.

I also recommend defining both your “desired” program scope as well as your current-state scope. The functions that make it into current state may initially be limited, but that gap from current to desired state can help define your investment and resourcing strategy and demonstrate that you’re planning for a more comprehensive security program.

Unless you luck out and end up with unlimited staffing and funding, you’ll always be faced with prioritizing new initiatives and projects due to resource and budget constraints. However much of budget prioritization comes down to filling gaps in your program’s capabilities vs. needs, so this scoping effort is a good way to start identifying what those gaps are. I plan to devote at least one future post to budgeting strategies.

A few more notes on scoping

Be specific

Once you’ve decided which high-level functions are part of your program (e.g. Identity and Access Management is in, Physical Security is out, etc.) you will want to further define the specific activities that you will be performing in each area. Again, control standards and best practices can help identify these discrete activities, though some of it will also depend on your organization.

For example, you may have decided that you will be responsible for Identity and Access Management – but what does that include? Is it Identity Governance or Privileged Access Management or Remote Access Management? How about Authentication? And for who? Internal workforce members? Vendors? Customers? All of the above? Are you setting the policy, defining the strategy, and managing all of the technology and day-to-day operations? If you’re not doing all of those things, who is, and how are the lines of responsibility and accountability drawn?

Similarly what would be your scope for something like vulnerability management? Is it just servers? What about desktops? Mobile devices? Is it only corporate devices or does it included personal devices too? Are you actually installing patches or just validating they were installed (or neither)? Perhaps your only responsibility is issuing the policy and standards.

I think you get the idea, but I’ve seen quite a lot of variability between organizations, so it’s not necessarily a one-size-fits all approach. Some of this may also be driven by the complexity of your environment. A multi-national organization with 100,000 employees and 1000 applications may have a different scope than a regional organization with 1000 employees and a relatively small technology footprint. It doesn’t mean both won’t have Identity and Access Management in their programs – but the scope and complexity of activities each CISO oversees may be different. Scope may also be influenced by the operational model, or by the organization’s culture and/or maturity.

Remember, you’re not defining projects or specific investments here, you’re defining the spectrum of activities your program will undertake.

As you’re defining this scope, I recommend actually writing out a scope definition for every component of your program. Here are some guiding questions to consider:

- What is the purpose of this component of the security program?

- What activities are in-scope?

- What activities are out-of-scope (and are they performed by someone else)?

- What technologies are in-scope and who manages those?

- Who else do you depend on to execute this function?

- Who or what is the target of your activities? (the specific users, technologies, or data)

- Who are your key customers / stakeholders?

- Here’s an purely illustrative (and simplified) example for Vulnerability Management:

- The purpose of the Vulnerability Management component of the security program is to ensure that all applicable software patching, updates, and system upgrades are performed in accordance with prescribed organizational standards and timelines in order to protect the organization from security threats and to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of organizational systems and data.

-

The activities that are part of this function of the security program are:

- Regular vulnerability scanning of the corporate network to validate patch compliance and supported software versions

- Regular external scans of all publicly-accessible systems

- Regular status reporting for IT system and business owners to ensure they have adequate visibility and to drive accountability with adherence to governing organizational policies and standards.

-

These activities apply to all endpoints connecting to the corporate network including servers, desktops, laptops and mobile devices. However, the level of scan and reporting detail may vary if the devices are not managed by the IT Department (and therefore can’t support credentialed scanning). These activities do not apply to personal devices connecting to the organizational guest wireless network.

-

Scanning activities are performed wholly by the Information Security Department using the ______ Vulnerability scanner (also configured, managed and maintained by InfoSec). Access to scan reports is provisioned by Information Security via _______ SIEM to all relevant IT and business stakeholders.

-

As this function serves only to validate vulnerability management practices, it also does not include any of the activities or technologies involved with actual system patch installation or upgrades, which are performed by the respective IT administrators.

This simplified scoping example doesn’t (and shouldn’t) detail the how but it does give a pretty good indication of what the scope of your vulnerability management activities would (and would not) include. And once you understand scope, you can then start developing the implementation approach (the “how”), which will in turn drive future projects, investment decisions, and resource requirements.

Don’t completely ignore the out-of-scope items

As I stated previously, be sure to document anything that falls outside of the scope of your security program – particularly anything that is required by law or understood to be a general best practice – and identify whether any other stakeholders within your organization are responsible for those functions (in part or in whole).

For example, you may have a separate department within your organization that is responsible for physical security, business continuity, or disaster recovery. Perhaps some of those responsibilities are shared amongst multiple departments, but all of it falls outside of your direct span of control and none of it is your responsibility to resource or manage. Regardless of who is responsible for these activities, if they’re tied to regulatory requirements, they still need to be performed properly. In the event of an incident or an audit, someone will be accountable, so it’s important to identify who that is (or isn’t) and whether or not your program shares any of that accountability.

Think of the security program as a risk management and resilience function

If you’re in an organization that is still in the early stages of defining (or redefining) what the scope of the information security program should be, my advice is to view it as a broader business risk function. Rather than seeing it as a “function of IT” or narrowly scoping it as only a governance/audit function, you should think about the security program in the wider context of “managing business risk” and ensuring “operational resilience”.

As such, perhaps it’s relevant to consider including activities such as configuration management, physical security, disaster recovery, and business continuity, in addition to more traditional activities like incident response, policies and standards, risk assessments, and identity and access management. Ironically, all of these functions have been included in security frameworks and best practices for years and are very much interrelated risk management activities, but many organizations still silo or split them across multiple departments and, in doing so, may be missing out on the benefits of a more holistic risk management strategy.

The security industry has matured and we’ve learned a lot of the last decade, so we should also be adapting and maturing the way in which we design and implement organizational security programs too. Modern information security programs can and should include a wide range of technical-, people-, data-, and business-focused functions, with a common governance structure and risk management strategy that aligns them all.

Organizing The Program

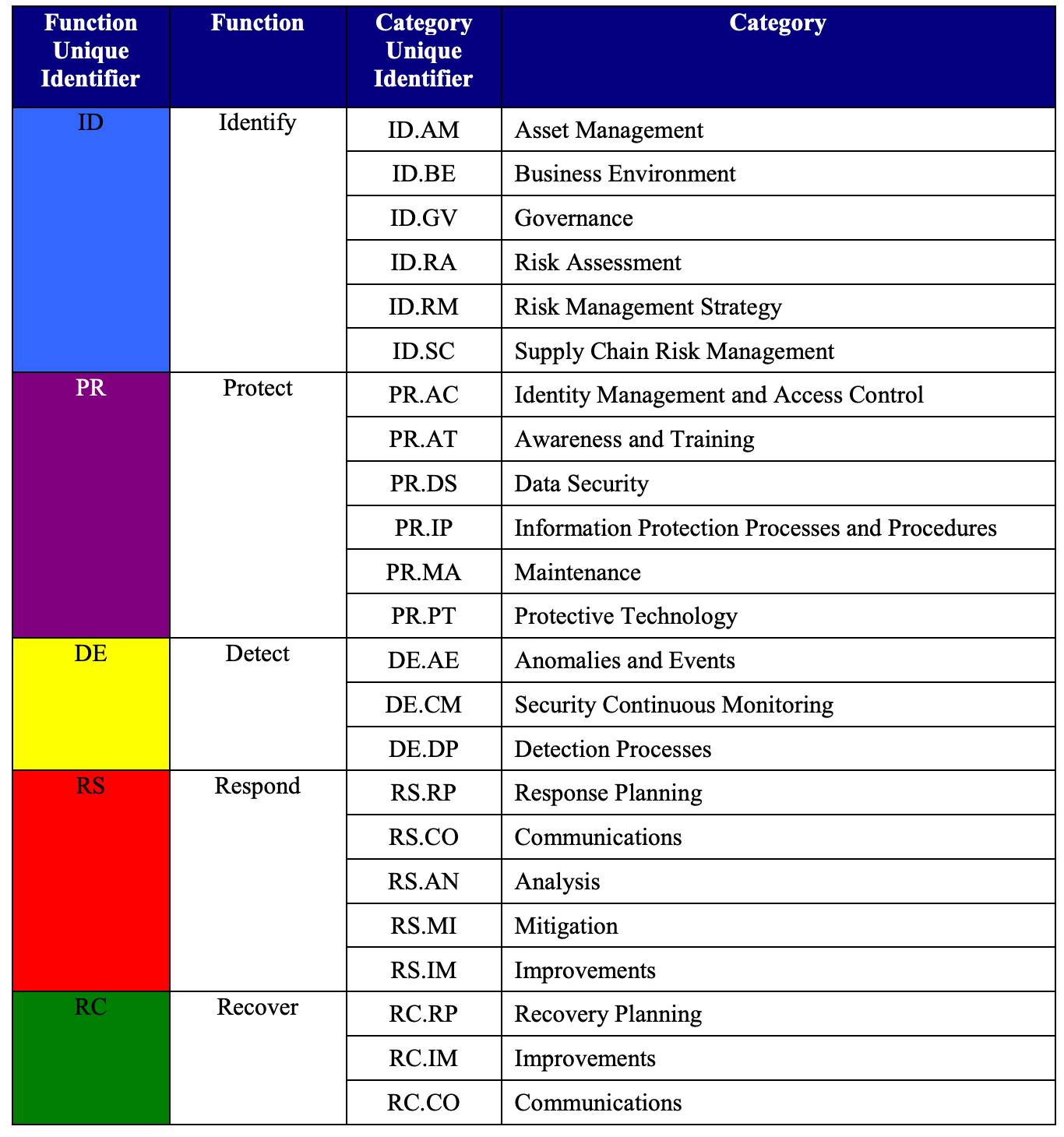

Now that you have a defined program scope, I recommend that you organize your program in some logical manner. It may sound like another very basic recommendation, but it will help you to better visualize, communicate, measure and track your program over time. I don’t particularly like the way that any of the control frameworks like NIST or ISO are organized but if you wanted to, you could leverage something like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, and align your initiatives as to whether they are meant to Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover.

The benefit of using something like CSF is that it’s already organized for you and you can clearly align and measure your program against best practices. However, I’ve found that even CSF is not comprehensive and some of the categories don’t map as cleanly as I would like. For example, does modern Endpoint Protection serve to Protect, Detect or Respond? I would say all three.

I personally like to organize the initiatives of a security program based on who or what they are primarily focused on protecting and enabling – e.g. people, processes, data, or technology.

Here’s an example:

A visual like this is something that even non-technical stakeholders and executives could look at and understand. And you can choose to add or remove layers of detail depending on the audience. Within those areas, you can further identify initiatives based on what they’re designed to do (protect, detect, respond, recover, etc.). A visual like this also helps demonstrate that Information Security is not limited to one area of focus (i.e. “IT Security”). Later, when it comes to measuring your program, you can also use a visual like this to help illustrate where you’re performing well and where you need to make additional investments.

Of course this is just a notional example. There are multiple ways to organize and visualize a security program and yours may look very different depending on scope. As I have done, you may also develop multiple ways to visualize your program, depending on the audience and the message. The most important thing right now is that you can clearly illustrate what is (and is not) within the scope of your program.

Closing Thoughts

At the end of your scoping exercise you should be able to clearly communicate all of the activities that are (and are not) part of your security program. The ideas I’ve outlined above are things that have proven useful to me but are not meant to be an exhaustive approach. There may be other sources you choose to reference … whitepapers, fellow CISOs, advisory firms, etc. Plus, your scope could change over time. Perhaps you don’t have the resources now to do everything you’d like to do. Perhaps there is a plan to absorb functions from other parts of the organization but that won’t happen immediately. For a number of reasons it’s very likely your program scope will evolve, but it’s important to clearly define current (and desired) state so that you can begin to plan initiatives around it.

Also remember the purpose of this scoping effort is to identify the functions and activities of your program, but it’s not going to identify specific projects or required investments. That comes from developing metrics and assessing your current state to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement. We’ll start diving into those activities next!

What’s Next?

So far we’ve covered the basic and fundamental activities of defining a mission statement, scoping and organizing a security program. In the next post, I’ll propose some key metrics that you may want to consider to help you demonstrate how well your program is designed, how well it’s performing, and to help prioritize projects and investments.

Stay tuned for more in this series. In the interim, I enjoy connecting with and learning from others, so reach out to me on LinkedIn and Twitter.